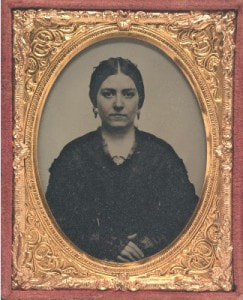

Mary Ann Brown Patten

Mary Ann Brown Patten

Boston's Mary Ann Patten was an American heroine every girl and young woman should know about, but few do. To this day, maritime experts assert that what Mary Patten did is next to impossible.

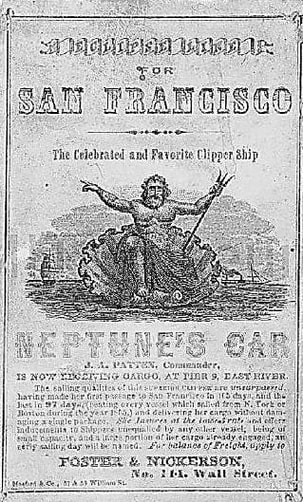

In 1856, nineteen and pregnant, Mary took command of a mammoth Clipper ship of 35 men, sailed through a hurricane, icebergs and a potential mutiny to safe port in San Francisco, all while nursing her dying husband, the Captain, back to health. She accomplished the impossible, because she didn't know she couldn't.

In the late 1990’s, Captain Charles Quinlan, a sea Captain from Portsmouth, New Hampshire, sought to build a replica of an American designed Clipper ship in East Boston, planning to use Mary’s speech to the crew that convinced them she could take command as part of an exhibit at the museum. More Clippers were built in Massachusetts than any other state, with the fastest – the Flying Cloud -- built by Donald McKay in East Boston. The Flying Cloud sailed from New York to San Francisco, traveling around Cape Horn, in a record breaking 89 days. With the California gold rush, the ships being built in Boston and throughout New England made it possible to travel from the east coast to the west coast in record time, bringing goods from all over the world, and helping turn San Francisco from a small fishing village to a thriving metropolis.

When I first learned of Mary’s story, I was inspired to write her speech. At a time when women’s voices were barely acknowledged, what could a girl of 19 have said to convince a crew of men, many of whom spoke different languages, to trust her to take command? Deep down I sensed the answer. With my husband and two young daughters, I lived off the grid and the proverbial beaten path, seven miles into the New Hampshire woods, in a house we built ourselves from the pines in the back yard. The winters battered us. We had a mile long snow covered “driveway,” but every day the girls had to get to school, and I had to get to work three states away. Each week, I spent Tuesday through Thursday in Connecticut, working as a psychotherapist in private practice, helping others navigate their own storms.

Before writing a word of her speech, I was introduced (by phone) to a writer from Connecticut by the name of Dave Goetsch. At the time, Dave was living in LA and writing for Third Rock from the Sun (he would eventually become an Executive Producer with The Big Bang Theory). Dave thought Mary’s story would make a great screenplay, and recommended that I read Christopher Vogler’s The Writers Journey, which applies the late mythologist Joseph Campbell’s work on the hero’s journey to screenwriting.

As a psychotherapist, I was already familiar with Joseph Campbell’s work, and ships were a back drop in my life. My ex-husband Chris was a maritime artist, and my office in Connecticut was literally right next door to Mystic Seaport. I could see the masts of the whaling ship, the Charles W. Morgan, from my office window, and two of my clients were ship builders who worked on the ship Amistad. Chris’ coffee table book American Maritime Paintings of John Stobart (his favorite painter) offered a luminous and meticulous portrayal of the era, helping me easily step back in time.

In 1856, nineteen and pregnant, Mary took command of a mammoth Clipper ship of 35 men, sailed through a hurricane, icebergs and a potential mutiny to safe port in San Francisco, all while nursing her dying husband, the Captain, back to health. She accomplished the impossible, because she didn't know she couldn't.

In the late 1990’s, Captain Charles Quinlan, a sea Captain from Portsmouth, New Hampshire, sought to build a replica of an American designed Clipper ship in East Boston, planning to use Mary’s speech to the crew that convinced them she could take command as part of an exhibit at the museum. More Clippers were built in Massachusetts than any other state, with the fastest – the Flying Cloud -- built by Donald McKay in East Boston. The Flying Cloud sailed from New York to San Francisco, traveling around Cape Horn, in a record breaking 89 days. With the California gold rush, the ships being built in Boston and throughout New England made it possible to travel from the east coast to the west coast in record time, bringing goods from all over the world, and helping turn San Francisco from a small fishing village to a thriving metropolis.

When I first learned of Mary’s story, I was inspired to write her speech. At a time when women’s voices were barely acknowledged, what could a girl of 19 have said to convince a crew of men, many of whom spoke different languages, to trust her to take command? Deep down I sensed the answer. With my husband and two young daughters, I lived off the grid and the proverbial beaten path, seven miles into the New Hampshire woods, in a house we built ourselves from the pines in the back yard. The winters battered us. We had a mile long snow covered “driveway,” but every day the girls had to get to school, and I had to get to work three states away. Each week, I spent Tuesday through Thursday in Connecticut, working as a psychotherapist in private practice, helping others navigate their own storms.

Before writing a word of her speech, I was introduced (by phone) to a writer from Connecticut by the name of Dave Goetsch. At the time, Dave was living in LA and writing for Third Rock from the Sun (he would eventually become an Executive Producer with The Big Bang Theory). Dave thought Mary’s story would make a great screenplay, and recommended that I read Christopher Vogler’s The Writers Journey, which applies the late mythologist Joseph Campbell’s work on the hero’s journey to screenwriting.

As a psychotherapist, I was already familiar with Joseph Campbell’s work, and ships were a back drop in my life. My ex-husband Chris was a maritime artist, and my office in Connecticut was literally right next door to Mystic Seaport. I could see the masts of the whaling ship, the Charles W. Morgan, from my office window, and two of my clients were ship builders who worked on the ship Amistad. Chris’ coffee table book American Maritime Paintings of John Stobart (his favorite painter) offered a luminous and meticulous portrayal of the era, helping me easily step back in time.

|

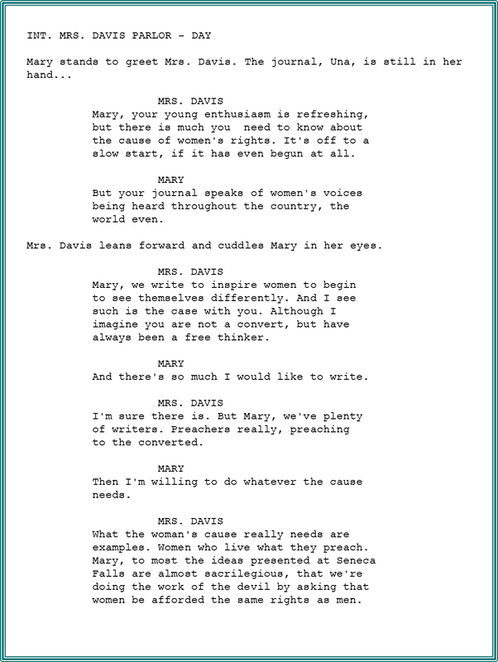

Outlining the script, I was struck with how neatly Mary's story fit into the stages of the hero's journey. This was not a fictional portrayal of the journey, like Star Wars or The Little Mermaid, for example. Mary truly lived the hero's/heroine's journey. After reading the completed draft of my screenplay The Widow’s Walk, Captain Quinlan gave it a stamp of approval from a sailing and historical perspective, then cried right in front of me, especially moved by Mary’s speech to the crew: "I know many of you aren't sure what to make of me, a woman, in charge. I know most of you doubt I can lead this ship. But gentlemen, we have to get this ship around the Horn, and I have to get my husband and child home, safely. You see, lads, our enemy here, is not these winter gales, not Captain Patten's brain fever, not even the devil, who some of you believe has put a woman in charge of this ship. No. Our enemy, gentlemen, is doubt." - Mary Ann Patten in The Widow's Walk |

|

After reading The Widow's Walk Dave Goetsch remarked that the script had "Oscar-winning dialogue for the right actress", and then referred the script to an agent at Creative Artists Agency. He considered taking it on, but told me point blank that he couldn't because I lived in New Hampshire. A friend knew a Vice President with the William Morris Agency who called the script "extremely well-written," but sent this feature film to the television division and to the very few cable channels that existed at the time. They all passed, as I knew they would. It was too expensive for television but, at the time, it was the only place to send a script with a female lead. A Connecticut production company (where Steven Spielberg's Amistad was filmed) offered to take an option on it, but I turned them down after my attorney said that in good conscience, she could not recommend going forward with this company, mainly due to their overall dismissive attitude. One moment stands out. I asked the Director what he loved most about this epic story about an American heroine, and he replied "the ship." A few years later, I discovered the company's President used The Widow's Walk as an example of the kind of projects they attract. |

A long time personal assistant to a former CEO of Marvel Studios declared “this movie must be made!,” then immediately warned me that the only way for it to be produced would be to find a powerful woman producer willing to fight for it. By this time, it was becoming clear to me that getting an expensive period piece with a female lead produced, especially as an unknown writer living outside of LA, was next to impossible.

Of course, that was the Hollywood culture of the past, and thankfully, things are beginning to change. With its women's rights theme, The Widow’s Walk couldn't be timelier.

Since I began screenwriting in my 40's, I was never interested in "breaking into Hollywood." From the onset, my passion has been to write heroine journey films that reflect the best of who we can be as women. As a psychotherapist and a mother, my deepest intention with The Widow’s Walk has always been to inspire young women:

"What words could I possibly use to convey to women to give away their love, not their souls?" - Mary Ann Patten in The Widow's Walk

Captain Quinlan never lived to see his dream to build the ship (to be called The Shining Sea, with a figurehead of Mary) come to fruition, and I’ve often wondered if I would endure the same fate with my dream for The Widow's Walk. I've been recently advised against admitting I wrote The Widow's Walk twenty -five years ago because a producer might think that means the story isn't relevant or that there's something wrong with the script, since it has yet to be produced.

The inherent message in such “advice” is to give up. Either I’m too old, the script is, or both. I learned the hard way what it means to be an older woman in a youth obsessed culture, yet those years and all their tests and trials have proven invaluable. They gave me the experience, courage, and battle scars to help me realize the best way for me to take the helm is by inspiring others to do the same.

I wonder if Mary felt the same, looking around the ship for a Captain when no one else had a greater desire than her to find a way to sail that ship home. Her husband was dying, and she was going to have a baby. Like Mary, when I began my journey, I was blissfully naive. Twenty-five years and several scripts later, I believe The Widow's Walk is still my best screenplay because back then, I didn't know I couldn't write a script of such caliber.

A former Commissioner of the Arts for the city of Boston once expressed to me how he wished he knew of Mary's story when they were deciding which Boston heroine to honor with a statue. A film provides a vibrant, and much more fitting tribute.

We all need to heed the lessons of the past; to learn from the women pioneers who came before us. The image on the big screen of a petite and pregnant young woman of 19 shouting out orders from behind the helm of a 216-foot mammoth Clipper ship is a powerful way to remind young women of what they too are capable of.

Of course, that was the Hollywood culture of the past, and thankfully, things are beginning to change. With its women's rights theme, The Widow’s Walk couldn't be timelier.

Since I began screenwriting in my 40's, I was never interested in "breaking into Hollywood." From the onset, my passion has been to write heroine journey films that reflect the best of who we can be as women. As a psychotherapist and a mother, my deepest intention with The Widow’s Walk has always been to inspire young women:

"What words could I possibly use to convey to women to give away their love, not their souls?" - Mary Ann Patten in The Widow's Walk

Captain Quinlan never lived to see his dream to build the ship (to be called The Shining Sea, with a figurehead of Mary) come to fruition, and I’ve often wondered if I would endure the same fate with my dream for The Widow's Walk. I've been recently advised against admitting I wrote The Widow's Walk twenty -five years ago because a producer might think that means the story isn't relevant or that there's something wrong with the script, since it has yet to be produced.

The inherent message in such “advice” is to give up. Either I’m too old, the script is, or both. I learned the hard way what it means to be an older woman in a youth obsessed culture, yet those years and all their tests and trials have proven invaluable. They gave me the experience, courage, and battle scars to help me realize the best way for me to take the helm is by inspiring others to do the same.

I wonder if Mary felt the same, looking around the ship for a Captain when no one else had a greater desire than her to find a way to sail that ship home. Her husband was dying, and she was going to have a baby. Like Mary, when I began my journey, I was blissfully naive. Twenty-five years and several scripts later, I believe The Widow's Walk is still my best screenplay because back then, I didn't know I couldn't write a script of such caliber.

A former Commissioner of the Arts for the city of Boston once expressed to me how he wished he knew of Mary's story when they were deciding which Boston heroine to honor with a statue. A film provides a vibrant, and much more fitting tribute.

We all need to heed the lessons of the past; to learn from the women pioneers who came before us. The image on the big screen of a petite and pregnant young woman of 19 shouting out orders from behind the helm of a 216-foot mammoth Clipper ship is a powerful way to remind young women of what they too are capable of.

"I feel afloat, wielding the helm of an even greater ship than the one of my childhood imaginings,

a ship of hope for women." - Mary Ann Patten in The Widow's Walk

a ship of hope for women." - Mary Ann Patten in The Widow's Walk